- Home

- Candace Havens

A Riveting Affair (Entangled Ever After) Page 4

A Riveting Affair (Entangled Ever After) Read online

Page 4

It was well into the afternoon before she had gathered all the items to be discarded into the hot air balloon basket and attached it to the back of a garbage disposal automaton, which obediently dragged it out of the room and down the servants’ stairs.

Some part of her was surprised that Sebastian hadn’t yet heard the commotion made by the various clockwork servants now cleaning the mansion, but she was nevertheless grateful. She suspected that when he did realize what was happening, he would be furious.

When at last she had organized the various tools and materials that remained, she marshaled the last of the automatons and set them to work within the laboratory itself.

She had just released a mechanical broom when the door swung open with a bang. The cat hissed. She looked up, her heart pounding so rapidly her blood roared in her ears. A strange, shameful thrill of anticipation ran through her. Sebastian stood in the doorway, his hair still rumpled from sleep.

He did not, however, look happy to see her.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing?”

Chapter Two

Sebastian had first stirred from his whiskey-induced slumber to the sound of whirring gears. It was a sound he hadn’t heard in five years, a sound that had sent rage coursing like corrosive acid through his veins.

He had fallen asleep in the armchair, where he’d sat down to finish off a bottle of Tennessee’s finest after Rose left. The anger, the shame, the unbearable self-loathing, had all come rushing back when she had seen him like that. Screaming like a child because of a bad dream, unable to even stand on his own without a cane—weak and pathetic, a broken, useless shell of a man. Drinking himself into a stupor had seemed the only way to escape the reality of what his life had become.

Now he wished he hadn’t. His head was pounding and the inside of his mouth felt as though it had been scraped with roughstone, but he forced himself to his feet, cursing his weak leg. He located his cane, then staggered into the hall.

He had to blink for his eyes to adjust to the light. Then he saw with rising disbelief that a clockwork servant was taking down the heavy velvet curtains of the hall and preparing to clean them. He was about to lunge for it when out of the corner of his eye he glimpsed a mechanical broom sweeping up dirt and debris into tidy little piles for its companion, a mechanical dustpan, to swallow.

“Greaves!” he roared, staggering down the hall so rapidly he nearly fell.

Where was the man? He knew how Sebastian felt about machines. Was the old fool finally losing his mind? Sebastian had tried to pension the faithful old servant off years ago, but Greaves, who had come to this house with his mother when she was a bride, had refused to leave Sebastian alone, and Sebastian hadn’t the heart to dismiss him.

Now Sebastian knew that he should have forced Greaves to retire years ago. As soon as Sebastian found the old man, he was going to blast him out of existence, and then put him on the first train to the country.

But Greaves was nowhere to be found. He wasn’t in the butler’s private quarters behind the kitchens. He wasn’t in the kitchen, in which the dozens of machines that had languished in the scullery for the past five years were once again clattering busily. He wasn’t in any of the places where he could usually be found.

Cursing, Sebastian climbed the stairs to the fifth floor, where the clockwork servants had been stored. His bad leg ached, but he didn’t pause until he had flung open the door of the room, expecting to see Greaves.

Instead he saw Rose Verney, her sleeves rolled to her elbows, and, to his bemusement, a cat at her feet.

She whirled around at the sound of his footsteps.

The cat hissed at him.

For a moment he stared at her, unable to believe that the chit had actually disobeyed him and refused to leave when she’d been told. Even more unwilling to believe that she had actually dared to turn on the clockwork servants he’d sworn he’d never use again.

“What the hell do you think you’re doing?”

She tilted her head, not looking in the least perturbed.

He could remember perfectly the way those lips had felt beneath his.

In the pale morning light, she was even more beautiful than she’d been by firelight. She’d piled her shining hair high, pushed a pair of his old brass goggles onto her forehead, and wrapped one of his heavy old leather aprons around her slender form.

He took a step toward her, uncertain whether he wanted to kiss her again, or shake her until her teeth rattled. Since both impulses seemed unacceptable, he settled for a snarl.

“I said, what the hell do you think you’re doing?”

He kept his voice soft, speaking in the tone that had once sent ashen-faced officers and terrified underlings scurrying to obey. Rose’s fingers trembled, but she made a visible effort to keep her voice steady.

“I’m fixing these last few clockwork servants,” she said. She bent to fiddle with the next automaton, a scrubbing machine. “It seems senseless to have so many, if you aren’t going to use them. Especially as you certainly don’t appear to have any human servants besides that very peculiar butler of yours.”

He moved across the room, and his hand closed over her wrist. “I didn’t give you permission to remain here, let alone to come up here and turn on the clockwork servants.”

She stilled beneath his touch, keeping her eyes downcast. Her lashes cast long shadows across her cheeks. “I suppose you didn’t. Nevertheless, I’m remaining, and as I’ll need a place to work, I have decided to use this room.”

“Perhaps I didn’t make myself clear last night,” Sebastian said. “I will not help you complete your father’s teleportation device.”

“Even if you do not help me, I intend to work on it, and I will need a laboratory. My sister Louisa sold my father’s house, and there is certainly no room in her home.”

“You will have to find a laboratory elsewhere. This house isn’t available to you. Now get out.”

“No, I don’t think I will. I have decided to remain here.”

For a moment he was speechless, unable to formulate a response in the face of such sheer effrontery. He tried to remember the last time that he, Sebastian Cavendish, had been so coolly disobeyed, and couldn’t.

He had been born to a vast fortune, his every whim since infancy catered to by a retinue of domestic servants. The power of that wealth had shielded him through his schoolboy days and then his years at Yale. Afterward, when he had joined the Union Army, he had been promoted rapidly through the ranks until he’d reached lieutenant colonel, and the officers who had served below him hadn’t dared to disobey even his lightest commands.

And yet this chit—this girl who looked barely out of the schoolroom—dared to challenge him?

“No?” repeated Sebastian softly. “Miss Verney, perhaps you do not understand me. If you do not pack up your belongings at once and depart this place, I will have you bodily removed.”

Rose raised an eyebrow. “I’d like to see you try,” she said, and switched the mopping machine on.

For a moment their eyes locked and held, his full of barely suppressed rage, hers full of a cool, calculating challenge.

He tried another tack.

“A gently bred young woman doesn’t just move into a single man’s home. It isn’t done. Your reputation will be shreds. If anyone knows that you spent the night under my roof, your reputation is already in tatters.”

She gazed scornfully around her. “I can’t imagine that you have any callers, sir, and as I have not told anyone where I am, who would know?”

He kept the rage out of his voice. “It isn’t wise for you to remain here. Even if your reputation is of no concern to you, are you not afraid for your person?”

“I’m not afraid of you.” Rose turned away from him to tidy up a workbench.

So that was it. She didn’t think he was truly a threat at all—only a cripple and a drunk, a man who feared shadows.

The thought sent another rush of rage coursing thro

ugh him. He lunged across the space that separated them, reached for her, and pulled her into his arms. He savored the expression of shock and surprise on her face.

“Perhaps you ought to be,” he said in a low, hard tone intended to terrify her. “I might be a cripple, but I am still a man, and last night you already obliged me to send away Mrs. Morrison’s girl.”

“You shouldn’t be consorting with that sort of girl in the first place,” she said. “It isn’t decent, and you could catch all sorts of nasty diseases.”

She was a little breathless, but she did not sound nearly as terrified as she ought to be.

He bent his head and kissed her.

He expected her to react with shock and fright, but her hands closed around the nape of his neck, her fingers clutching at his hair. The kiss was every bit as potent and heady as the one they had shared the night before, and it was a long, dazed moment before he could lift his head and gaze down at her.

She looked up at him with an expression akin to pity. He felt as though he had been punched in the stomach.

At their feet, the cat hissed at him again.

“Now, if you are quite done, Mr. Cavendish,” Rose said. “I have work to do.”

…

As Sebastian stalked away, after a final contemptuous glare that would have reduced a lesser woman to tears, Rose cleared off the table she had selected for her use. Her heart beat a rapid tattoo.

She hoped he hadn’t seen how badly her fingers trembled as she had set aside glass beakers and coils of wire when he first entered the room.

He was just trying to frighten her, she told herself firmly. He had made it clear that he wanted to make her go away.

Unfortunately for him, he wouldn’t be so easily rid of her.

Though she would have liked to begin work on the teleportation device immediately, she knew that she would need to attend to the house first. Producing a small stack of foolscap and a fountain pen of her father’s invention, she set out to survey the rest of the mansion to see what must be done to make it habitable again.

The cat still at her heels, she walked through the rooms of the upper floors, making her way slowly through each story before going down to the one below, reviewing the work of the automatons, unjamming those overcome by too many years’ worth of dust or debris. As she walked, she made a list of the things that would need to be cleaned, repaired, or discarded.

The fifth floor contained, in addition to the former nursery she intended to commandeer as a laboratory, a series of small, narrow bedchambers meant to be servants’ quarters. These rooms would need to be properly swept and cleaned to dislodge the mice, spiders, and other small denizens that had taken up residence beneath the furniture and in the tucked-away corners.

On the fourth and third floors, she counted fifteen bedchambers and nearly as many bathrooms, none of which were inhabited save for Sebastian’s room, and all of which were filthy beyond belief.

No wonder he had become such a crank. She wondered why he didn’t hire human servants. Even if he had developed an aversion to using machines, surely he could afford a few housemaids and a hall boy or two?

It was nearly twilight when she finally made her way to the first floor. She came first upon the ballroom, which was filled with more broken bits of machinery and what looked like the remains of a flying machine that had crashed mid-flight. A pair of massive double doors at the end of the room opened onto a circular dining room, which in turn led to a smaller gallery.

When she opened a second set of the gallery, however, she came to a dead halt.

She was staring into a rose garden.

Her lips parted. Had she somehow opened a door that led outside? Instead of open sky above her, clear panes of glass served as the ceiling. An indoor courtyard, then. But this was unlike any she had ever seen before.

Moving as though in a dream, she went from vine to bush, leaning to sniff each rose she passed. She stopped when she came to the center of the courtyard. Sebastian knelt in the dirt, attacking weeds beneath several bushes. He was shirtless, his arms streaked with mud, his shoulder muscles rippling. In the cool purple twilight, he looked like a lost prince from a fairytale.

Unable to stop herself, she drew closer. He threw aside a handful of weeds and looked up from his rosebush.

“Mr. Cavendish,” she said.

He straightened, and that was when she saw the mass of twisted scar tissue on his chest, directly over his heart.

Her gaze flew up to his. His expression was utterly impassive. She flushed and searched desperately for something to say. “This is the loveliest garden I have ever seen in my life.”

“What the hell are you doing here? I thought you were setting up your cursed laboratory on the fifth floor.”

“I intend to do that next, yes,” Rose said. “Did you plant all of these?”

He nodded curtly.

“This is such an unusual place to plant roses,” she said. “I have never heard of an indoor garden. Has this always been here?”

“No,” he said. And then after a moment, he added, “I needed something to do. After the war.”

He picked up a dirty white shirt he had left on the floor and used it wipe the sweat and dirt from his face and his hands. Rose suddenly understood.

Greaves had told her that this courtyard had once held his laboratory. He had torn it out, ripped the very floor apart to find the good earth beneath, and replaced his life’s work with this garden: a growing, living thing that could not maim or kill.

She took a deep breath, watching him. “If you wanted something to do,” she said, “you could build my father’s teleportation machine with me.”

He didn’t answer. Stalking past her, he left her alone in the gathering dusk, surrounded by the fragrance of a hundred roses.

…

Over the next few days, Rose had no time to work on the teleportation box. Instead, she devoted herself fully to setting up the laboratory on the fifth floor and making the rest of the Cavendish mansion fully habitable once again.

It was work harder than any she had ever known before, as mistress of her father’s modest home in New Haven, as a nurse during the war, as an unpaid drudge in Louisa’s home. From the library to the portrait gallery, from the music room to the ballroom, she shepherded Sebastian’s army of clockwork servants through the grueling task of transforming Cavendish House.

Though the automatons performed most of the manual labor, they required supervision, as well as constant repairs. Fortunately by the second morning, Greaves, creaky and ancient as ever, gathered his courage, presented himself to her, and put himself at her disposal. He was pleased as a child at the notion of Cavendish House being restored to its former glory, and they consulted together on the rooms that would be kept closed, and the rooms that would be in use. They created lists of the foods and supplies they would require delivered on weekly basis, and of the new furnishings they would need.

It wasn’t until the fifth morning that Rose, waking in a freshly cleaned bedchamber to a breakfast prepared by a clockwork cook, presented by a clockwork butler, could finally return to the fifth floor. The cat, which she had named Ashputtel, followed her upstairs to her laboratory, where she composed a long letter to Jenny, assuring her friend that she was safe and would remain in New York for some time.

Afterward, she pinned her father’s blueprints to the worktable. She was so absorbed in her work that when the laboratory door banged opened, she jumped.

Sebastian stood in the doorway.

She hadn’t seen him since the night in the rose garden. He looked as bad-tempered and unkempt as ever, but she noted with pleasure that his clothes, at least, were clean, if badly rumpled. She and Greaves had repaired the machines in the laundry room, and Greaves had been retrieving Sebastian’s dirty clothes from his bedchamber.

“Good morning, Mr. Cavendish,” she said coolly, though her heart had once again set up its violent rhythm at the sight of him. “Have you had breakfast yet? The

cook made eggs this morning. No doubt they will be stone cold by now, but they’re in the kitchen if you’re hungry.”

“I never eat breakfast,” Sebastian said.

She gave him a severe look over her shoulder. “You’re just as bad as Father was. He always said he couldn’t be bothered to remember to eat in the mornings, not when the whole day was waiting for him.”

She spread out the rest of the blue prints, and as she worked, she willed Sebastian to look at them. To see the design and the mathematics and the puzzle of it, and grow intrigued. But when she glanced up, he wasn’t looking at the blueprints at all.

He was looking at her.

Her stomach curled with sensation. A sudden memory of his kiss burned on her lips. To hide her confusion, she gathered up the supplies she would need to build the box. This, at least, she knew how to do. She had watched her father work on the box for too long—and burn through too many models—to not know how to reconstruct its initial steps.

She managed to gather the majority of what she needed before Sebastian spoke again.

“You are determined to stay here.”

“Yes.” She dragged several huge slabs of glass to the center of the room, where she had already gathered a chair, innumerable coils of wire, a large magnet, and a wooden pedestal.

“You are determined to build your father’s teleportation device,” Sebastian said. He gazed down at the first page of instructions and illustrations.

“Yes.”

“And nothing I say or do can persuade you to leave?”

“Not until I’m finished.”

He studied the blueprints, and she pretended not to notice.

“I was afraid of that.” His voice was absent.

Rose risked a glance at him. He had picked up a pencil to jot some kind of mathematical equation beneath one that her father had written. Not wanting to disturb him, she picked up several heavy coils and a pair of pliers to connect the first of the wires to the chair.

She had watched her father complete this process so often that she did it without consulting the blueprints. By the time Sebastian looked up, his brows furrowed in concentration, she had succeeded in suspending a piece of burnished copper above the chair.

Bet Me to Stay

Bet Me to Stay Model Marine

Model Marine She Who Dares, Wins

She Who Dares, Wins A Case for the Cookie Baker

A Case for the Cookie Baker Lions, Tigers, and Sexy Bears, Oh My!

Lions, Tigers, and Sexy Bears, Oh My! Truth and Dare

Truth and Dare Charmed & Dangerous

Charmed & Dangerous Charmed & Ready

Charmed & Ready Dragons Prefer Blondes

Dragons Prefer Blondes A Riveting Affair (Entangled Ever After)

A Riveting Affair (Entangled Ever After) Christmas with the Marine

Christmas with the Marine Make Mine a Marine

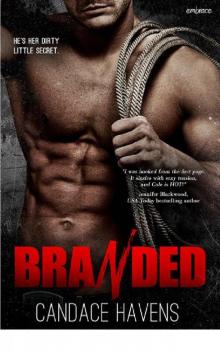

Make Mine a Marine Branded

Branded Her Last Best Fling

Her Last Best Fling Take Me If You Dare

Take Me If You Dare Mission: Seduction

Mission: Seduction Baby's Got Bite

Baby's Got Bite Take It Like A Vamp

Take It Like A Vamp Like a Charm

Like a Charm